The most exciting things happening in science, technology and business are happening where fields converge – at the intersections and edges. The divisions between formerly separate industries are breaking down and the real opportunities for growth are where those industries interconnect. Self-driving cars don’t just need automotive engineers, they also need people who understand software, traffic engineering, the psychology of drivers and regulatory processes.

And if everything is connected and interdependent then we are going back to the idea of the polymath: the generalist not the specialist. The most innovative developments of the future, in business, science and the arts, will come from creative generalists who blend unique disciplines with technological skill sets. The continued success of today’s organisations, companies, and communities will depend on individuals capable of solving problems by thinking outside the proverbial box. T-shaped individuals who combine specialist knowledge (the down bar of the T) with a broad understanding of other domains (the crossbar) and how they combine for greatest effect.

George Murray’s study of the most significant scientists found that 15 of the 20 were polymaths:[1] Newton, Galileo, Aristotle, Kepler, Descartes, Huygens, Laplace, Faraday, Pasteur, Ptolemy, Hooke, Leibniz, Euler, Darwin and Maxwell were all generalists. Darwin developed his ideas about evolution by drawing on disciplines from geology to zoology. A contemporary example of a polymath is Elon Musk, who has combined an understanding of physics, engineering, programming, design, manufacturing, and business to create several multibillion-dollar companies in completely different fields.

Yet, despite the need for polymaths, such individuals are quite rare. That’s because society has traditionally promoted specialisation over generalisation. The history of human labour has been one of increasing specialisation. In the days of the hunter-gatherer every member of the tribe would have been expected to be proficient in every task. As we progressed however, from agricultural to industrial and now post-industrial economies, workers have become increasingly specialised, based on a long-standing assumption that the more deeply you specialize, the more easily you can find well-paid employment.

There was a time in the 14th to 16th centuries that polymaths found favour – Leonardo da Vinci’s Renaissance Man. However, we soon reverted again to the specialist, not just for its economic benefits but also for the specialist’s undoubted contribution to the advancement of knowledge. We need specialists but we also need polymaths, generalists who offer three distinct advantages.

The Polymath Advantage

- The avoidance of bias. Specialisation has undoubtedly been important for the advancement of knowledge. But one of the dangers of such specialisation is that it often coincides with cognitive bias. The process of overlooking potential solutions because of erroneous assumptions and established patterns of thought. Groupthink is a common phenomenon in political, business and scientific spheres. We need people who can see beyond the bias of their cherished idea, single discipline or department.

- Innovation comes from the edge. The most creative breakthroughs come from atypical combinations of skills and knowledge. Brian Uzzi, a professor at the Kellogg School of Management, analysed more than 26 million scientific papers going back hundreds of years and found that the papers with the most impact often had teams with atypical combinations of backgrounds. In a second study he found that the top performing studies also cited atypical combinations of other studies: 90% conventional citations from their own field and 10% from other fields. We need people who can bridge the gaps between disciplines and departments, and act as idea translators.

- Complex ‘wicked’ problems require multi-disciplinary approaches. Many of the greatest challenges currently facing individuals and society benefit from solutions that integrate multiple disciplines. Climate change, for example, will require us to transform the way we generate, store and use energy, and the ways in which we manage more extremes of weather and climate. For that we will need to integrate our meteorological understanding with our understanding of ecological systems, human psychology, the built environment, as well as financial and socio-economic factors. We need people who can identify and champion the synergies between disciplines and departments.

In short, polymaths bring the best of what has been discovered across various fields to help them be more effective in their core specialisation. They build atypical combinations of skills and knowledge across domains and then integrate them to create breakthrough ideas and even brand new disciplines and industries. And this isn’t just an aspiration for those wishing to be pre-eminent scientists or multi-billionaire business leaders. We can all benefit from becoming polymaths, from becoming more T-shaped, and it is easier than it might sound.

Becoming a Polymath

There is too much knowledge in the world today for one person to know everything that is known, like Leonardo Da Vinci’s ‘Renaissance Man’. But it is possible to create a network of ties that allow you to learn from people in other disciplines and become sufficiently knowledgeable in more than one discipline. To become, in other words, a competent generalist or polymath. In short, anyone who loves learning across fields can use it to be more successful in their life, career and discipline.

And the good news is that it’s easier and less time consuming to become very good at a few things than superlative at one. Few people will create paradigm shifting scientific theories, write a culture defining novel, or become a multi-billionaire businessman. But everyone has at least a few areas in which they could, with some effort, be in the top quartile. And it’s the combination of two or more skills at which you are competent, but not exceptional, that can lead to a powerful skill set.

The reason why it is easier to learn broadly than deeply lies in the Pareto Principle (the 80/20 rule) and the work of Jake Chapman[2]. Vilfredo Pareto was an Italian economist and his principle is that 80 percent of effects come from 20 percent of causes. In other words, a small portion of work produces the majority of the results.

Researchers have found the Pareto Principle operating in many areas, including wealth distribution, employee productivity, customer revenue and agricultural yields. However, as humans, we are predisposed to linear thinking, which makes the implications of his power law distribution hard to get our heads around, but the implications are clear. An organisation could focus on satisfying the needs of only 20 percent of their customers and still maintain 80 percent of their revenue. Imagine what it could do with the resources it saved?

What is less well known and even more mind-bending is that the 80/20 rule is also divisible, meaning that where the 80/20 rule applies, it is also true that 20% of 20% percent of the inputs (4%) generate 80% of 80% of the outputs (64%), and so on. In other words, the 80/20 dynamic gets more lopsided and more powerful as it progresses. For example, with only three further steps you arrive at 0.16% of inputs being responsible for 41% of output. That is astonishing force multiplication!

The principle has several applications, but it’s particularly useful when seeking mastery in something new, which is where Jake Chapman comes in. He believes that the Pareto Principle is at its most interesting when thinking about our growth potential as human beings.

Imagine, he writes, if you had 100 units of learning to assign to various skills throughout your life. How would you spend those points? Do you spend all of them in one subject and try hard to become a true subject-matter expert? Or do you diversify your skill set, trying to make yourself into a well-rounded person? The Pareto Principle says that you will overwhelmingly get more added value if you spread those points around.

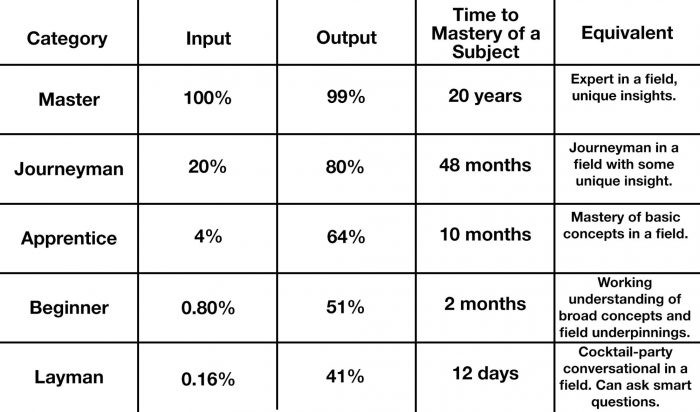

In an article published in TechCrunch, Chapman broke the process into five stages (see the diagram below):

Assuming that achieving mastery of a subject takes 20 years of dedicated training, he then works backward applying the 80/20 rule. In applying the 80/20 rule to developing ourselves, we see that 80% mastery could be achieved in 20% of the time. And if someone were to spend 0.16% of 20 years (12 days) in focused study of a subject, they should be able to achieve cocktail-party mastery (if you remember them, think ‘Bluffer’s Guide’ competence). Similarly, someone who spends 0.80% of 20 years, about two months, while still being deemed a novice could be ready to begin a career in the field. For example, a layman entering the Google coding boot camp can graduate a couple of months later prepared to enter the job market as a software developer.

While the numbers aren’t a precise representation of learning, my own experience (cramming for exams, moving jobs and roles, and writing my PhD) suggests that they are about right. The point is, if learning follows a broadly Pareto distribution, then there is value in diversifying your skill set. Chapman is not suggesting it will be easy, but it is easier than at any other time in the history of mankind. Anyone with internet access and a sincere desire to learn can access abundant information with the click of a button: LinkedIn, Babbel, Khan Academy, edX, iTunes U and so the list goes on.

The Practical Benefits

Chapman concludes with the practical benefits of applying the Pareto Principle to your life and learning, to which I have added my own thoughts to come up with the following four benefits:

- Enhance your contribution. The diversity of a polymath brings the benefits discussed in my previous article: reducing cognitive bias, increasing innovation and coping with wicked problems. All of which are valuable in our personal and professional lives.

- It’s never too late.One particularly empowering implication of the Pareto Principle is that it is never too late to get a new start in life. As an example, someone could pick up cybersecurity as a specialty, spend 4 years on the subject and have 80 percent the proficiency of a lifelong expert. This is particularly relevant in technological fields because old learning is quickly being rendered obsolete.

- Level the playing field.For people who learn more slowly than others, they can apply the Pareto Principle to level the playing field. While the gifted graft for the last bits (20%) of insight in a single field, learners who play the game can quickly accumulate a broad set of skills and insights to help them succeed.

- Learn with intention.Finally, it is important to learn with intention. Many people stumble from place to place in life, simply letting their lives and careers develop organically. With the deep specialist knowledge of artificial intelligence gobbling up many jobs lifelong learning becomes a necessity not a choice.

One Final Thought

The examples I gave of polymaths were all men, where are the women? A quick Google search for examples of polymaths brings up men, you have to search specifically for female polymaths to get any suggestions. It’s not hard to guess the reasons why, but who would you propose, past, present and future (having read this article you may wish to include yourself)?