In a world where things are moving much faster than ever we need more leadership from more places. Where things are more complex, more ambiguous, and more interdependent, we don’t have time to wait for everything to go up the chain of command and back down again. We need more people to step up and lead, more people taking leader-like actions so that organisations can better handle complexity and ambiguity and react more quickly. So how do we find them?

I start from the belief that not everyone in a formally appointed leadership role is actually a leader. Some people who have leader or manager in their title never lead. In my experience, if you meet a group of employees in any organisation and ask them, have you ever had a boss who didn’t lead? Most hands will go up. And that’s not necessarily the fault of the ‘failed’ leader. Too often people are promoted because they are good at their job, not because they display any leadership potential.

Equally, some people have the qualities of a leader but do not see themselves as such. Subordinates may have those qualities, but if they think there’s only ever one leader in a group, and they have a boss, then she’s the leader. They are not even thinking about leadership as part of their identity. Sometimes people need someone else to see leadership in them and make a point of telling them.

To identify leaders we could make a list of the qualities that make a leader, but that can be a tricky and rather fruitless exercise: creating a shopping list of characteristics that is far too idealistic to be credible or achievable. The way through this is to recognise that fundamentally leadership is something that others see in us. People grant a leader that identity by their willingness to follow them. In which case, if we can identify who people follow we will have found our leaders.

In the normal run of things we talent spot leaders by asking existing leaders and managers to identify those among their teams who lead, or have the potential to lead. The disadvantage with this approach is that you may be asking somebody with few, if any, leadership qualities to identify that which they don’t possess themselves. Alternatively, you may get clones of your existing leaders, because they recognise only the qualities that they do possess, or you get the promotion of favourites.

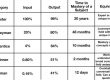

A more objective method, and one that accords with my belief that followers are best qualified to identify leaders, is to survey the whole team, department or organisation. I do this using Social Network Analysis (SNA) software, using it to locate the most influential individuals in an organisation, particularly those who are not represented in the formal hierarchy of leadership. The process is straightforward and asks each team member two simple questions alongside a drop down list of other team members.

1. “Who do you confide your concerns about sensitive work-related issues?”

2. “Who do you go to get knowledge, information or advice needed to perform your job?”

In my experience, these two questions, which focus respectively on trust and respect, give an excellent indication of who people follow. No matter the individual qualities of a ‘leader’, if those qualities engender trust and respect you have a real leader. And it’s not just me. There is evidence to support this belief.

Amy Cuddy, a Harvard Business School professor, has been studying first impressions (how people size you up), for more than 15 years, and has discovered certain patterns in these interactions. In her book, “Presence”, Cuddy says that people quickly answer two questions when they first meet you: Can I trust this person? Can I respect this person?

Psychologists refer to these dimensions as warmth, or trustworthiness, and competence, respectively, and as a leader you want to be perceived as having both. Interestingly, Cuddy says that most people, especially in a professional context, believe that respect, or competence, is the more important factor. But her research reveals that warmth, or trustworthiness, is actually the key to how people evaluate you. And from an evolutionary perspective this makes sense.

In our early history as a species it was more important to figure out if a stranger was going to kill you and steal all your possessions than if they were competent enough to build a good fire. While competence is highly valued, Cuddy says that it is evaluated only after trust is established. If someone you’re trying to influence doesn’t trust you, you’re not going to get very far.

Furthermore, focusing too much on displaying your competence can backfire. A warm, trustworthy person who is also competent elicits admiration, but only after they have established trust does their competence become a gift rather than a threat. But ultimately we need both trust and respect for people to follow us. It is no good being competent if people expect you to stab them in the back (if only metaphorically these days), but neither is it any good to be utterly trustworthy if you can’t manage your way out of a paper bag.

Now, with the answers to our survey in hand, we could just present the results as a list of potential leaders, but SNA software allows more dynamic and contextual 2D visualisations of the group surveyed, one for trust and one for respect. These images comprise nodes (coloured squares or circles) that represent people and ties or edges (black lines connecting them) that indicate who trusts and respects whom. The bigger the node, the more people in the team, department or organisation who see that person as a leader. Someone worthy of their trust and respect.

Some will be existing leaders, and you can congratulate yourself on good talent spotting. Others may already have been identified as having potential. But be warned, there will be surprises. Some of your leaders won’t really be leaders at all and others with genuine potential will have gone unnoticed by you and themselves. In a complex and fast-paced world that is not a mistake that organisations can afford to make.